As I write this article, it is less than fifty years since the American military conceded defeat and withdrew from Vietnam. The wound is still raw and bloody for both parties

So I’m surprised that in the week before I arrive in Da Nang, the US Navy is there ahead of me. For the first time since 1975, America has a military presence in Vietnam but this time, it is a political handshake and public relations show to illustrate a newfound camaraderie. Make no odds about this, it is extraordinary – the one-party communist state of Vietnam’s new best friend is the Trump-led capitalist car-crash freak show, the US of A.

Given the still unresolved differences triggered by the US Navy’s previous visit to Da Nang, I know I am watching a little piece of history in the making and I’m sorry I’m not already there to witness it. I’m delighted, though, as I’m watching the CNN newsreel, to get a WhatsApp message from the woman I’ll be meeting in a week’s time; Truong Duy Nhat Phuong, and it’s a photo of her on the flight deck of the USS Carl Vinson. Evidently, I have connections in the right places.

Phuong, aka ‘Ti’, is my guide and translator for my tour of Vietnam. A native of Da Nang, Ti has prepared me for my visit with stories of her home country including her family’s experiences during and after the America-Vietnam War. It is not easy listening.

Ignored and betrayed

After the First World War, when Vietnam was part of France’s Indochina ‘empire’, Ho Chi Minh was part of the political group Groupe des Patriotes Annamites (The Group of Vietnamese Patriots) petitioning in Versailles at the peace talks (1919-1920) for his country’s autonomy.

Vietnam was part of a combination of south-east Asian countries invaded and occupied by France since the late 1800s. The Western practise of invading and occupying countries populated by people not of European descent was more prevalent then than it is now. Sadly, though, it still happens to this day with the USA being the biggest offender.

Which is ironic because Ho Chi Minh thought the Americans would understand and respect the Vietnamese people’s call for self-determination. It seems Ho Chi Minh had thought his own peoples’ struggle would be seen by the Americans as synonymous with their own ‘war of independence’. Perhaps, if it were the French colonists in Indochina rebelling against their homeland’s taxes, they might have gained more sympathy from the Americans.

He was ignored by both the French and the Americans. When WWII broke out the Japanese invaded Vietnam and the French collaborated in order to maintain their own occupation of the country. America sort help from Ho Chi Minh and his Vietnamese independence movement, the Viet Minh, to assist their forces in fighting the Japanese. The Americans promised support for independence with democratically elected self-rule once the war was over.

They lied.

When the Viet Minh defeated the French, the Americans did not see the Vietnamese winning their independence, they saw the Soviets expanding communism

At the close of WWII, with the Japanese defeated, the French invaded Vietnam again but this time with the backing of American money. The US picked-up in excess of 70% of the costs of France’s invasion. Fighting against the combination of old-school imperialist French military might (Yes, I know, but bear with me) and the capitalist imperialism new money of the Americans, Ho Chi Minh and his Viet Minh were very much the Asian David to the Western Goliath.

When the Viet Minh defeated the French in the First Indochina War in 1954, the Americans did not see the Vietnamese winning their independence, they saw the Soviets expanding communism. The subsequent American invasion divided the Vietnamese in a civil war and ultimately, divided the American people too.

Pay the price

Travel blogger ‘Nomadic Matt’ declared in 2010 that he would never return to Vietnam on account of being fleeced by street vendors and cab drivers because of being American. It was not about the money, he protested, but a lack of respect. He wrote:

‘The Vietnamese are taught that all their problems are caused by the West, especially France and the United States and that Westerners “owe” the Vietnamese.’

During the 20 years of their military intervention in Vietnam, the Americans dropped three times the number of the bombs dropped in WWII by all the combatants combined. With indiscriminate bombing campaigns and chemical weapons, the American military aimed to destroy the infrastructure of both urban and rural landscapes with scant regard for civilian casualties.

Since US troops left in 1975, over 40,000 Vietnamese have been killed by unexploded ordinance

The Vietnamese don’t need to be taught anything about the damage America has done to their country, they live with it every day. Since US troops left, over 40,000 Vietnamese have been killed and many more injured by unexploded ordinance. Vast tracts of land remain unsafe from the estimated 350,000 tons of unexploded bombs scattered on the surface, and toxic on account of the defoliants sprayed over it. How many Vietnamese suffer from disabilities and ill-health owing to the chemical weapons used by the US no one knows because no one has collated the data. The US government still denies that the defoliants are toxic to humans.

Well, to civilians. After protracted legal action, the US government was forced to concede liability and now pays out to the US servicemen who suffer from poor health as a consequence of being doused with toxic chemicals by their own airforce. To this day, though, the US government still refuses to acknowledge responsibility for the consequences of its actions in Vietnam and has offered no assistance in repairing the damage its military actions caused.

A different story

Imagine if the Vietnamese had been granted autonomy at Versailles at the end of WWI. The Americans would have had to fight hard against the old imperialism of Europe but they’d done that before and as the strongest military and economic power in the world, it would have been an easy win.

What if, instead of funding the French reinvasion of Vietnam, America had supported Ho Chi Minh and spent that money funding the building of a free Vietnam?

If not then, then after WWII. With Vietnam liberated from the Japanese by the Viet Minh fighting alongside the Americans, they were in the perfect place to be the heroes of the moment. The French had now been rescued from German occupation twice in wars in which American forces had been instrumental in victory. What if, instead of funding the French reinvasion of Vietnam, America had supported Ho Chi Minh and spent that money funding the building of a free Vietnam? Imagine the political, social and economic influence America would have in Vietnam today if it had chosen to be as instrumental in its freedom as it was for the French.

The American-Vietnam war need never have happened. If the Vietnamese people feel that the scars their country bears are the faults of the Europeans and the Americans then it is because this is true.

As Ti and I explore the 9th-century ruins of the beautiful Cham dynasty temples at My Son, I point out a distinctly 20th-century artillery shell casing stood neatly among the temple columns. ‘What’s that doing here?’ I ask. ‘They dig them up all the time,’ she shrugs.

Da Nang

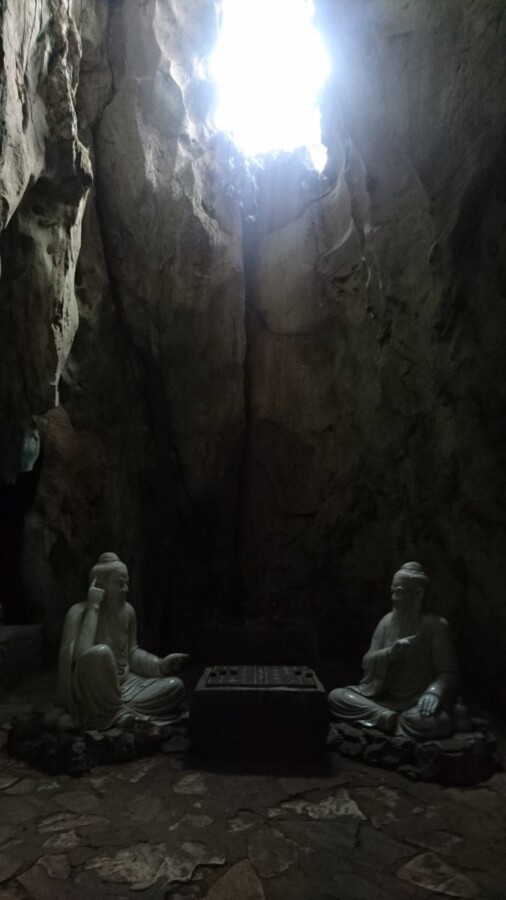

I arrived in Vietnam at Da Nang in March. The beach was clean and cool with the breeze off the South China Sea taking the edge off the humidity. I was there outside of school holidays but nonetheless, was amazed how many tourists weren’t crowding the beach. Often, it felt like I had all of it to myself. If you want more than just soaking up the sun, Da Nang has plenty of interesting sites in and around it. Ti showed me the Marble Mountains, the Lady Buddha and the Cham Sculpture Museum by day and fine dining and dancing by night.

Hue

For my first tour, Ti booked one of the many available in the leaflets in the hotel. The tours are comprehensive, taking care of your travel, food and admission for all of the stops on the tour. They pick you up and drop you back to your hotel and are so cheap it is not worth converting the cost into your own currency.

Our trip took in a number of stops but the top billing goes to the ancient capital city at Hue and the Tomb of Khai Dinh.

Hue was the capital city of the Nguyen Dynasty, from 1802 to 1945. A 19th-century citadel, it is surrounded by a moat and stone walls and encompasses the Imperial City with its palaces and shrines and the Forbidden Purple City – once the emperor’s home.

All this ancient and beautiful history is marked with the far more recent sort. Hue was the scene of one of the most bloody battles of the American-Vietnam war when the Viet Cong seized control of the city in its 1968 Tet Offensive. There then followed three months of hand-to-hand fighting as the Americans re-occupied Hue, street by street. The scars of these battles are clear to see in the buildings that survived.

Tomb of Khai Dinh

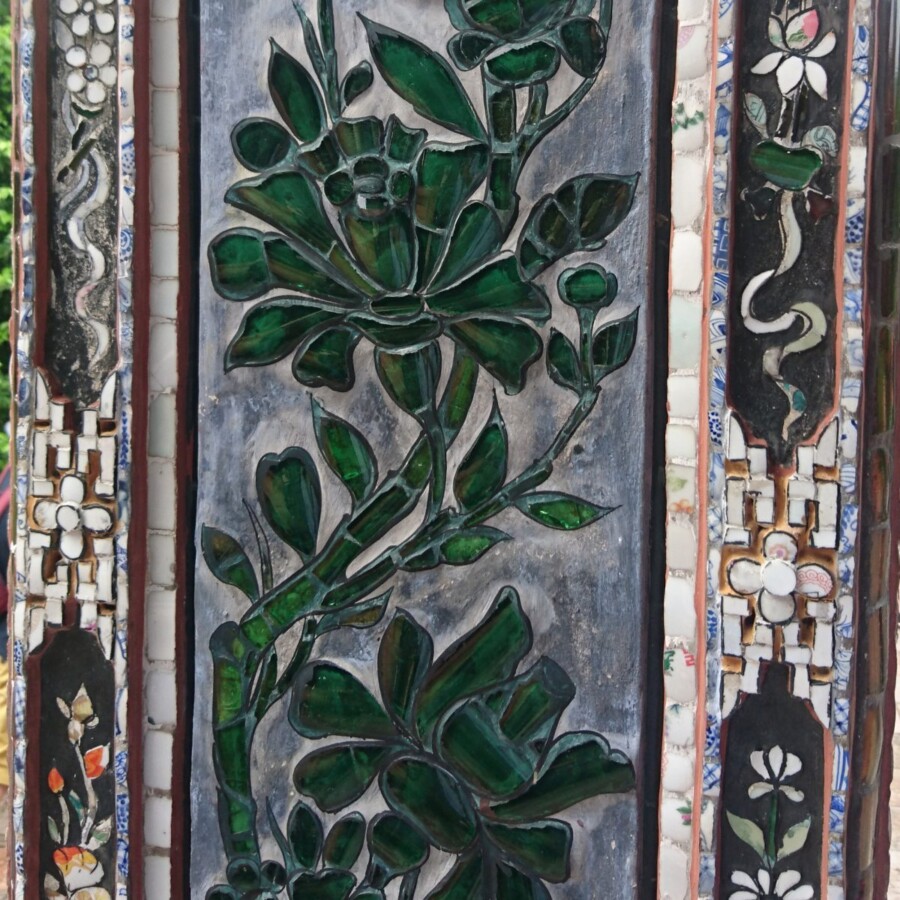

Built on the steep hillside of Chau Chu Mountain, not far from Hue, the tomb is a beautiful building set amongst breathtaking views. Khai Dinh was the 12th Emperor of the Nguyen Dynasty, reigning from 1916 to 1925 and he was not a wholesale success. A puppet of the French government he was seen by his countrymen as a collaborator. In 1922, the political activist Nguyen Ai Quoc (who would become known as Ho Chi Minh) wrote a play about Khai Dinh called ‘The Bamboo Dragon’ that lampooned him as all talk and no trousers.

He wasn’t gay but his boyfriend was. He had several wives and fathered a son but he advised new recruits to his harem that they were joining a convent. He loved all things European, especially French, and his tomb is the craziest mixture of European and Asian architecture – like Versailles on LSD. Khai Dinh levied heavy taxes on his countrymen to pay for this very expensive tomb and that, along with his collaboration with the French, made him deeply unpopular.

My Son

A short drive south of Da Nang is My Son, a site of ancient Hindu temples dating back to the 4th century, a place for religious ceremonies and royal burials for the Champa dynasty. The Cham people are thought to have been descendants of seafarers originating in Borneo and they settled and ruled the land that is now southern Vietnam. Many of the southern Vietnamese identify with and cherish their Cham heritage and see themselves as both physically and culturally different from their northern countrymen.

The buildings at My Son are being preserved and protected with support from UNESCO having been recognised as a World Heritage Site.

Hoi An

This town has a history as a trading port dating back to 200BC. At its height in the 18th century, Hoi An was trading as far afield as Egypt and was considered the centre of the world for Asian traders. Hoi An became a backwater in the 19th century. A combination of political changes and the river it sits on, Thu Bon, silting up, saw its role as a major international trading port sequestered by its neighbour, Da Nang. The town became a snapshot of the past and, ironically, this preserved it.

During the American-Vietnam war, this quiet bywater did not attract the attention of the American airforce and so survived largely unscathed. Now, Hoi An’s old town is a UNESCO World Heritage site recognised as a living preservation of an ancient South-East Asian town. The town thrives as a tourist must-see and movie location scout favourite and with its streets, festooned with lanterns, it’s not hard to see why.

Hanoi

I stayed in Hanoi only briefly, just two nights wrapped around a trip to Halong Bay. I was in the heart of the old town, within walking distance of Hoan Kiem lake and its beautiful, ancient temple and surrounded by the most eclectic mixture of what modern Vietnam is: I found a fitness class one evening performing line dance routines on the bank of the lake illuminated by the ancient, Taoist temple, Ngoc Son.

By night and day, the streets are dirty, cramped and chaotic. In the UK, we like to joke about planning regulations and health and safety but in truth, we know it makes sense. Visit Hanoi and you’ll see what life is like in a town unburdened by such things as traffic controls and building regulations.

I took one of the walking tours which included a visit to the Maison Centrale, a prison built by the French invaders in 1913 to incarcerate the Vietnamese campaigning for independence. Subsequently, the prison was used by the Viet Cong to house American prisoners of war who famously christened it the ‘Hanoi Hilton’.

It is a fascinating and exciting place and I thoroughly enjoyed my time in Hanoi but equally, I would not stay there too long.

Halong Bay

There are a couple of places I have been on my travels where I have looked out at the landscape and thought; ‘This is not planet Earth – I’ve lived on it all my life and it doesn’t look anything like this.’ Halong Bay is one of those places. The landscape is so different to any other place on the planet that it is extraordinary and don’t take my word for it, Halong Bay is considered to be one of the new, seven wonders of the world.

The place is a tourist hot spot and it gets very crowded. The excursion into the ‘Surprise Cave’ was not unlike being in Holborn tube station in the rush hour and on the return leg of the cruise when, clearly, the boats all drop their borders at much the same time, it did feel a little like a Dunkirk reenactment.

Having said that, our evening on Halong Bay was very quiet and peaceful. A strong breeze during daylight necessitated much hanging on to hats but as the sunset, the wind died and the place was so quiet the English travellers felt obliged to whisper. The last photo in this gallery, of me drinking a G&T before changing for dinner, illustrates perfectly why I want to visit again and stay longer.

Reasons I’ll return to Vietnam

It is a beautiful and intriguing country with friendly people and, for a Londoner, it is insanely cheap with English widely spoken.

With Ti as my tour guide and historian, and my own reading, I knew more than a typical tourist might about Vietnam before I visited. Nonetheless, the country felt utterly unknown to me; it was a fascinating, alien landscape. My visits to Hue, Hoi An and My Son felt like teasers, I could have happily spent much longer exploring.

I found everything so cheap – taxis, food and drink, the hotels – so much so that pretty early into my trip I stopped bothering to calculate the exchange into pound sterling. I had the advantage of Ti but I did spend some time exploring by myself and if anyone charged me ‘tourist rates’, I did not notice and would not have begrudged them anyway.

Vietnam feels like a country finding its feet in a new era of peace and prosperity. After the American-Vietnam war ended, Vietnam was plunged into another ten years of armed conflict with its neighbour; Cambodia. That ended in 1985, so the country is not yet fifty years into the longest peacetime it has seen in centuries.

Tourism is already big business and growing. Everywhere I went, I saw development and investment, from new seafront hotels at Da Nang to the archaeological renovations of the temples at My Son.

Vietnam is still a one-party communist state but the old-school totalitarianism is softening a little, you can WhatsApp and Facebook – though be careful what you post. Nonetheless, if I was an entrepreneurial sort, I’d be in Vietnam starting up a new business venture right now. As a wandering writer, though, I’m happy to visit, scribbling in notebooks and drinking dry martinis that cost less than a London espresso.

A Perfect Stay

I stayed at the Homestay Sea Kite hotel while I was in Da Nang and it was a perfect combination of big, modern hotel facilities but with personal, boutique service. I really felt like I was a friend of the family come to visit. No affiliates referral here, just my heartfelt opinion. Oh, and the hotel is only a three-minute walk from My Khe beach.

Find the Homestay Sea Kite on:

Further reading

This is by no means a comprehensive bibliography of my research of Vietnam but is reading I would recommend to anyone planning a visit or simply interested in knowing more.

- The Vietnam War Is Still Killing People – The New Yorker

- The Vietnam War Is Over. The Bombs Remain – The New York Times

- Ken Burns: How Vietnam War sowed the seeds of a divided America – The Guardian

- The Vietnam War – Ken Burns & Lynn Novick

- The Girl in the Picture: The Story of Kim Phuc, the Photograph, and the Vietnam War – Denise Chong

- US aircraft carrier in Vietnam for historic visit aimed at Beijing – CNN